We sat in the waiting room. The backs of my legs squeaked against the leather chair. I was fidgeting, my heart pounding. My husband reached over and grabbed my hand. The gesture startled me, but I was happy he was there for me as we waited for the doctor. Finally, my name was called and my husband lifted me from my seat and guided me into the exam room. I vaguely remember the sound of the doctor entering. Tests were done. Poking and prodding ensued. Photographs were taken. Finally, the doctor had come to his verdict. The ophthalmologist declared me blind. A long, grueling battle with breast cancer throughout my twenties had wreaked havoc on my body. Chemo, radiation, and steroids had saved my life but caused irrevocable damage to other areas — including my optic nerves.

There I was, a 32-year-old, Ivy League-educated woman, thrust into darkness. I was no longer Holly, the competent wife, and social worker. I had been bestowed a new label, “disabled,” which to me had a very negative connotation at the time.

Adapting to My Disability:

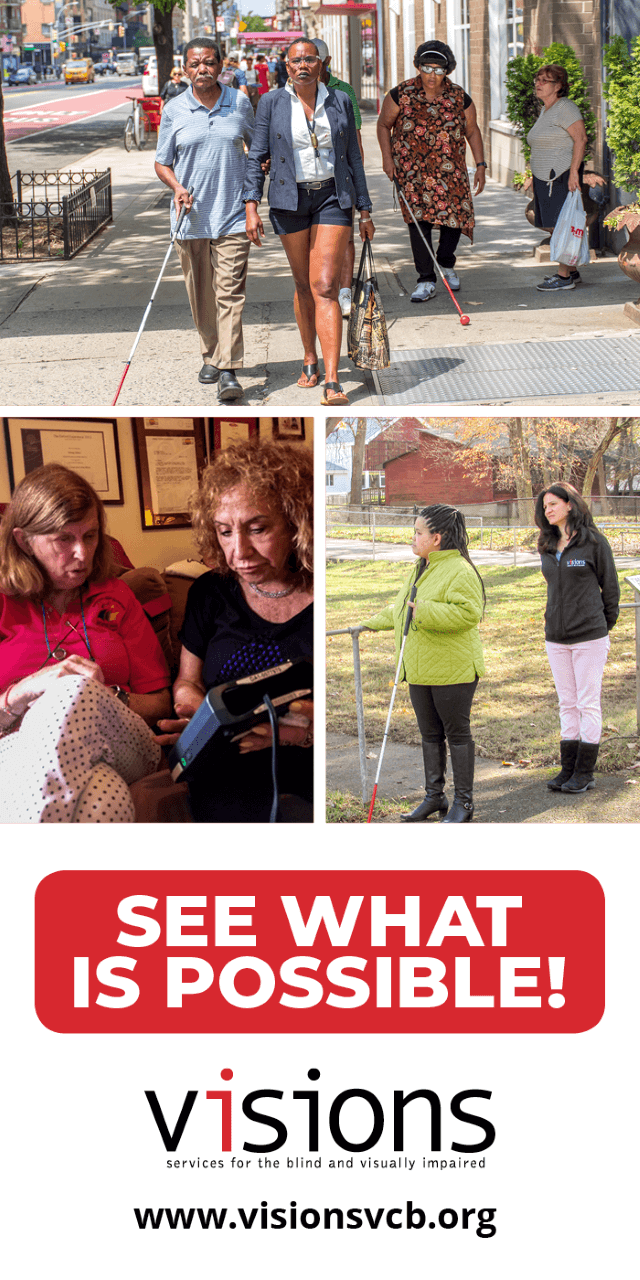

Over the next several months, I began receiving various services from different blindness organizations to help me adapt to my new disability. I had to re-learn everything from using the stove to doing laundry.

By far the hardest obstacle to overcome was orientation and mobility training. Using a combination of my hearing and an aluminum white cane, I had to learn how to cross the street and board a bus. It was absolutely infuriating to me. I was angry at everyone from my husband to God, but the person who got the brunt of my attitude was my mobility instructor, Carol.

After completing a route one afternoon, Carol and I sat in my kitchen. We scheduled our next training session and she commented on my bad attitude.

“What do you want, Holly?” she asked.

“What do you mean what do I want? I want to be able to see.”

“Well, we both know that’s ‘not’ going to happen. So what else do you want for your life? What do you dream of being?” Carol asked.

Without even thinking, I answered, “A mother. I’ve always wanted to be a mom.”

“It’s possible, Holly.” she said.

“No, it’s not, you don’t know what I’ve been through.”

“Well, I know you’ve been through more than most, but blind women can and do have babies,” she said.

Battling Infertility:

Just like breast cancer, infertility is a disease and one in eight couples are affected by it. My husband and I had suffered multiple miscarriages over our ten-year marriage. Each loss was more heartbreaking than the last.

My gynecologist attributed my infertility to a combination of my cancer treatments and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal imbalance that causes insulin resistance and prevents regular ovulation. I had been put on a high dose of Metformin to help regulate my periods and decrease some of the PCOS symptoms. Despite taking my medication regularly, doctors said there was less than a 2 percent chance I would ever conceive and carry a healthy baby to term. It would take a miracle.

When I brought up the topic of having children with my doctors after entering remission from my cancer; I was met with constant disapproval. My complicated medical history prevented IVF from being a viable option, and I was advised not to harvest my eggs for surrogacy. Domestic adoption agencies were unlikely to accept our application for the same reason. Financially, we were absolutely strapped from all the other medical costs that we had incurred thanks to cancer.

Now that I had been declared blind, the consensus was “I just needed to be blind” and forgo the idea of motherhood altogether. It felt like I wasn’t even supposed to talk about it.

But Carol, the ever-patient mobility instructor, had reminded me that it was okay to speak about my desire to have children. I could talk about my infertility.

Infertility Does Not Discriminate:

Breast cancer survivors “can” battle infertility.

Visually impaired women “can” suffer from infertility.

There is such a negative stigma attached to parenting while sick or disabled that people forget infertility can still be an obstacle. My infertility wasn’t a “secondary issue” in relation to my vision loss and cancer. PCOS was a “co-occurring” medical condition preventing me from becoming pregnant.

Society must remember there are no definitive rules that dictate who gets to attain the coveted role of mother. Infertility does not discriminate. This merciless disease doesn’t care who you know, how much money you have, or what hardships you’ve already been forced to endure.

Why should any of us feel ashamed to talk about our infertility?

I sought emotional support through counseling. I focused on the “now” and vowed to be more patient with myself as I made the transition from the world of the sighted to the world of the blind. I began to open up to my husband about some of the frustrations I was experiencing. Finally, I asked God for strength because that’s what I needed at that moment, strength.

Small Victories and Big Miracles:

Six months I worked with my orientation and mobility instructor. Three times a week, one hour a day. With practice, I was able to cross the street. I could make it to the mailbox. I was able to walk the 16 blocks to my local pharmacy to pick up my eye-drops. Small victories happened for me every day, both emotionally and physically.

A few days after graduating from mobility training, a trip to my doctor for what I thought was a stomach bug, revealed I was pregnant. After a rough first trimester, we successfully made it to our 20-week anatomy scan.

Our precious little girl was developing normally and although considered very high risk, this once infertile, cancer survivor turned blind woman, had defied the odds. My precious miracle baby was born in February 2013. One year later, we welcomed a second daughter into our family.

In my wildest dreams, I never imagined I would have the privilege of hearing another human being call me Mommy. Despite its challenges, and there are many, parenthood should never be taken for granted. Those of us who have lost a child or struggle with infertility know what I’m talking about.

If you are blind or visually impaired and suffering from infertility, don’t be ashamed to ask for help. Speak to your doctor and reach out to organizations like Resolve, the National Infertility Association. Established in 1974, Resolve, is a nonprofit organization with the only established, nationwide network mandated to promote reproductive health and to ensure equal access to all family building options for men and women experiencing infertility or other reproductive disorders.

Don’t let blindness be the barrier preventing you from discussing concerns relating to your infertility. If you truly want to become a parent, take the steps necessary to connect with the medical professionals and supportive networks that may help you in your journey.